There is so much being made about the mystique of

Kirill Petrenko, the seemingly otherworldly 47-year-old conductor from Siberia who began his tenure as Berlin Philharmonic music director last weekend, that it hardly seems like mystique at all anymore. The fact that he does not sell himself has been made a selling point. The New York Times has dubbed him the anti-anti-maestro (does that make a maestro?).

He shies away from interviews and is said to be truly shy, a rare and you would think undesirable trait for a conductor. He is also said to leave his ego, if he even has one, at the stage door. Again, it is said (everything comes secondhand with Petrenko), that rather than genuflect before the greatest orchestral machine the world has ever known, as many a maestoso maestro has for the most sought-after job in the profession, Petrenko was genuinely surprised to have been selected by the players, who pick their music director themselves.

So was the music world. Petrenko had never before headed an orchestra, only opera companies and only one big one, Bavarian State Opera in Munich, where he remains for two more seasons. He is a perfectionist uneasy with recordings, of which he’s made few, yet he heads an orchestra that has long been a leader in audio and video recording and now concert streaming with its outstanding Digital Concert Hall. Petrenko, say those who know him and love him (that seems to go hand in hand), has music for breakfast, lunch, dinner and a

nightcap.

After hearing Petrenko bring his Berlin Philharmonic to the Salzburg Festival, after it performed Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in Berlin’s Philharmonie and in a free outdoor concert in front of the Brandenburg Gate for 20,000, I’m not so sure I buy the mystique business. The ego issue is clearly complicated. But his two concerts in the Festspielhaus in Salzburg, the first a repeat of the Beethoven Ninth and second featuring a performance of Schoenberg’s Violin Concerto with Patricia Kopatchinskaja of speechless greatness, left no doubt about just how special Petrenko is.

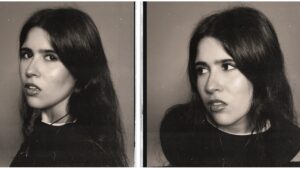

Violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja performing with the Berlin Philharmonic at the Salzburg Festival.

(Stephan Rabold / Berlin Philharmonic)

He is a small man with a black beard from Omsk, Siberia, a town known for its munitions industries, petrochemical plants and freezing winters. At 17 he immigrated with his family to Germany and went on to study in Vienna. He worked his way up through German opera companies, first in Meiningen, then at the Komische Oper Berlin

(where he happened by to succeeded by Pacific Symphony Music Director Carl St.Clair) and then in Munich (where he followed two other SoCal notables, Zubin Mehta and Kent Nagano).

Although he has had little exposure in the U.S., Petrenko did conduct the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl a dozen years ago in an all-Russian program. He didn’t make much of an impression. (The Bowl, with its minimal rehearsal schedule, seems about the

worst place possible for this meticulous anti-anti-maestro.) For that matter he only conducted the Berlin Philharmonic a few times before the 2015 announcement that he would succeed Simon Rattle.

On paper it looks as though Petrenko will not continue Rattle’s 16-year effort to bring the Berliners into the 21st

century, an effort that included making John Adams a composer in residence and inviting Peter Sellars to stage Bach passions. Petrenko will make limited appearances this year, giving prominence to Beethoven, Mahler and standard Russian repertory. There is little new or even unusual. But we shouldn’t be too fast to draw conclusions about a Petrenko we barely know.

Before the Beethoven Ninth on Sunday, Petrenko programmed Berg’s suite from his sexually provocative opera, “Lulu,” which ends with the grisly sounds of Lulu being killed by Jack the Ripper in London. It was just a coincidence, maybe, but a month earlier Brexit party officials turned their backs on the playing of “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth, because it is the anthem of the European Union. There was no coincidence here. Petrenko understood that an ode to joy is never without doubt.

On this occasion, “Lulu,” which featured soprano Marlis Petersen, had a sad and sensual, but never sensational, quality. Petrenko conducted with a beatific look on his face, a warm smile, Dalai

Lama-like, showing not so much happiness but serenity, even in the face of doubt and tragedy. Yes, of course, Petrenko has an ego, and surely a tremendous one. You don’t control the huge 100-plus egos that make up this phenomenal orchestra by chance. But what might make him unique among conductors is the way Petrenko uses his ego to transcend it.

Rather than demonstrating Beethoven’s extraordinary capacity to manufacture joy out of nothingness in the Ninth, for instance, Petrenko was more like the great Sufi singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

. He waved his arms, like he were dancing, as Khan

did when he sang. In a fast and dazzlingly virtuosic performance that lasted barely over an hour, Petrenko seemed like he was after a spiritual awakening to the joy that is the dance of the cosmos.

The symphony zipped by, without our attention directed to the obvious big moments, as if Petrenko didn’t want to tell the listener how to think. There was, though, just enough rapture and climax to indicate that something out there just beyond your grasp. That second sense kept building and building, without you quite realizing how and why, no matter the familiarity of the material. By the end of the buildup, you found out what a hypnotic performance this had been all along, that joy was a concord to be felt by all.

The next night was the same but also a very different Petrenko, because the music was different. For the Schoenberg concerto, written in the 1930s when the composer taught at UCLA, Petrenko gave up his ego to his inspired soloist. This can seem dauntingly complex music, but Kopatchinskaja breathed new and unexpected life into every phrase. This time, it was not the cosmos the listener was transported into but Schoenberg’s psyche, in which each fleeting thought, each neuron fired, proved a theatrical event. The concord of chaotic mental states, it turns out, can be an even greater revelation.

Next to this concerto, Tchaikovsky’s fate-bemoaning Fifth Symphony can seem transparent and manipulative. Yet in a hugely dramatic and probing performance, Petrenko created surprising depth. He dug beyond the oppressive ego of Tchaikovsky, beyond indulgent melodrama, beyond the showoff insecurities.

Here,

Petrenko was not fast but slow, so slow that Tchaikovskian pathos lost its pretense. Here Petrenko’s tool was power, and climaxes were ear-shattering. Here the Berliners’ playing was of such beauty and passion and perfection that Tchaikovsky had no place for subterfuge. Here was Petrenko placing his ego not at Tchaikovsky’s disposal but ours, showing us how to hear beyond the superficial into our deepest being.