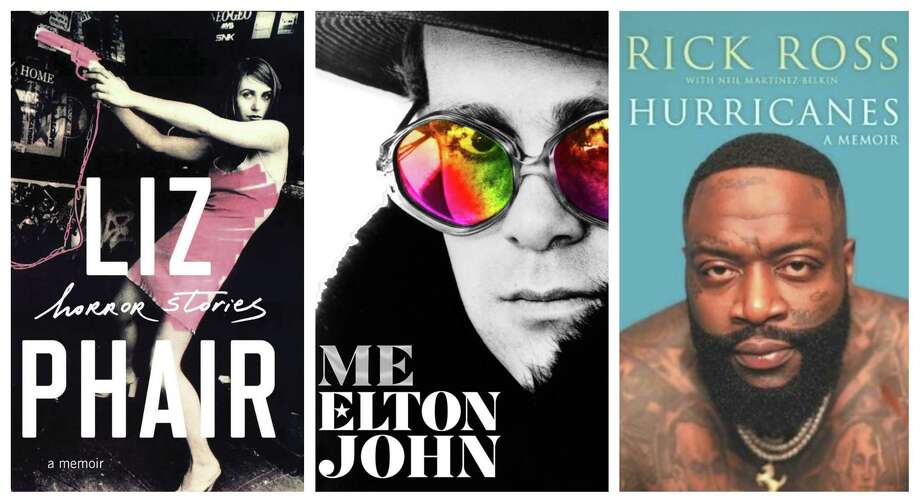

Horror Stories; Me; Hurricanes

Horror Stories; Me; Hurricanes

Photo: Random House; Henry Holt; Hanover Square Press, Handout

Photo: Random House; Henry Holt; Hanover Square Press, Handout

Horror Stories; Me; Hurricanes

Horror Stories; Me; Hurricanes

Photo: Random House; Henry Holt; Hanover Square Press, Handout

Book World: In recent memoirs, musicians reveal glamorous tantrums, plenty of drug use and the double-edged sword of fame

The first time Elton John tried cocaine, he threw up. Looking back, he thinks, this should have been a sign. “It’s hard to see how I could have been given a clearer warning unless it had started raining brimstone and I’d been visited by a plague of boils,” writes John in his unsparing, extravagantly funny new memoir, “Me.” Nevertheless, he kept at it, eventually losing 16 years of his life to addiction.

Because cocaine aggravated his existing anger issues, John spends a lot of “Me” yelling at people: He throws a glamorous tantrum on a private plane in front of Stevie Wonder. He screams at people because he doesn’t like the weather. He is forever storming out of places, only to storm back in.

Even in his worst moments, John seems merely like a charming malcontent, thanks in no small part to journalist Alexis Petridis, whose work shaping the memoir’s narrative voice is uncredited. Not since Keith Richards’s memoir, “Life,” has any rock legend seemed such good company.

“Me” traces John’s pre-fame childhood in suburban London, his distant father and terrifying mother, and his early interest in rock ‘n’ roll, but doesn’t linger. It’s not long until he touches down in California, a 23-year-old virgin who will soon become the biggest pop star in the world.

John discovers he’s gay, to no one’s surprise but his own, and after ending an abusive relationship, embarks on a series of fast-burning love affairs that soon curdle into resentment and boredom. He marries a woman (“What if I’d only spent the last fourteen years sleeping with men because I hadn’t found the right woman yet?”), unsuccessfully.

As in most rock star memoirs, the fame years are the best years. John is an energetic collector of celebrity friends, and “Me” doesn’t stint on detail. John Lennon is a beloved friend and drug buddy. Queen Elizabeth slaps a viscount. Sylvester Stallone and Richard Gere come to blows over the affections of Princess Diana. Freddie Mercury and Michael Jackson argue over a llama.

He is benevolent toward almost everyone, except for his mother, who is glowering and unkind, and Tina Turner, an imperious she-devil who tells him he looks fat in Versace, which is possibly the worst thing you can say to Elton John.

John eventually meets young AIDS patient Ryan White, who inspires his advocacy work and pierces his veil of self-pity and privilege. He gets sober, survives prostate cancer and meets and marries David Furnish; the couple has two sons.

“Me” feels bracingly honest, which it must. Because readers bond to their memoirists like hostages to their captors, trust is essential. In his new memoir, “Hurricanes,” rapper, drug boss and label head Rick Ross plays with the idea of an unreliable narrator, with mixed results. Growing up in southern Florida during the ’80s cocaine boom, Ross got close enough to the hustlers in his neighborhood to realize the straight and narrow held little appeal. He left college to pursue music, and after 10 years of struggle and mid-level drug dealing, landed three No. 1 albums in a row. He established a record label, Maybach Music Group, then bought several Wingstop fast-food franchises and Evander Holyfield’s palatial Georgia estate.

His career was almost derailed by his persistent seizures (likely caused by exhaustion, and his love of codeine), and by the revelation that he briefly spent time as a correctional officer in a Florida prison, a fact he omits until more than halfway through what is an otherwise chronological book.

“Hurricanes” is a straightforward, conventional memoir, until it isn’t. In the book’s last pages, Ross hints that there are larger forces behind his success, or at least behind his fortune, that he isn’t at liberty to discuss. He asks: How is he, the survivor of so many murder attempts, able to move through the world without fear? How can he afford the Holyfield estate, with its wallet-melting upkeep and stable of horses, when he’s only had one platinum album? (“Do you have any idea how much it costs to take care of four horses?”) Something is fueling his extravagant lifestyle, Ross hints, broadly, and it isn’t being a Wingstop franchisee. It’s a strange non-revelation that casts the rest of the book into question. Whatever he’s withholding, even Ross seems to acknowledge it’s too big a thing to leave out. “I can’t tell you,” he writes. “Forgive me for that.”

Frankness is Liz Phair’s brand. Her 1993 breakthrough album, the brilliant and profane “Exile in Guyville,” chronicled her post-college experiences in Chicago’s male-dominated music scene. Phair’s new memoir, “Horror Stories,” makes little mention of the album, or of her artistic life (likely the subject of a separate book), though it examines the repercussions of the fame “Guyville” wrought.

Less a linear memoir than a series of episodic reminiscences stretching from her childhood to the present day, “Horror Stories” is harrowing and deft. It’s a catalog of things Phair wishes she had done differently: the drunk girl in the bathroom she didn’t help, the wrenching relationship with an ex who was probably a sociopath, if she had to guess, the man on the bus leveled by her disdain, the affair that ended her marriage. “We hurt our spouses, our kids, our reputations, for nothing,” Phair writes of the latter. “Empty lust: a cardinal sin.”

In one chapter, she struggles with an unnamed producer who sounds a lot like Ryan Adams. He hits on Phair, who declines his advances, though she worries he’ll lose interest in finishing her album if she doesn’t sleep with him. “I suspected from the way he blew hot and cold that without that extra kick of excitement, that frisson, his own interest in the project wouldn’t last.” This is mostly what happens.

There’s a moment in every celebrity memoir when the celebrity realizes that fame has become a trap, a gilded bubble from which they must escape, although nobody ever actually does. Phair blames success for her loneliness and self-centeredness, but it’s too appealing to give up. For John and Ross, fame protects, providing bodyguards and layers of staff. But Phair is half in and half out, famous enough to draw celebrity stalkers and feel isolated from her friends, but not famous enough to be able to retreat behind mansion gates. While John is so cocooned that washing machines have to be explained to him, Phair pushes her own cart at Trader Joe’s, flirting with the cashier to bolster her flagging self-esteem.

John might argue that she has the better end of the deal. The farther you get from the person you originally were, he writes, the unhappier you’ll be. Fame corrodes. “It’s a grotesque, soul-destroying environment to live in,” he writes. “And you’ve created it yourself.”

—

Stewart writes about pop culture, music and politics for The Washington Post and the Chicago Tribune. She’s working on a book about the history of the space program.