Published

8:25 am PST, Wednesday, November 27, 2019

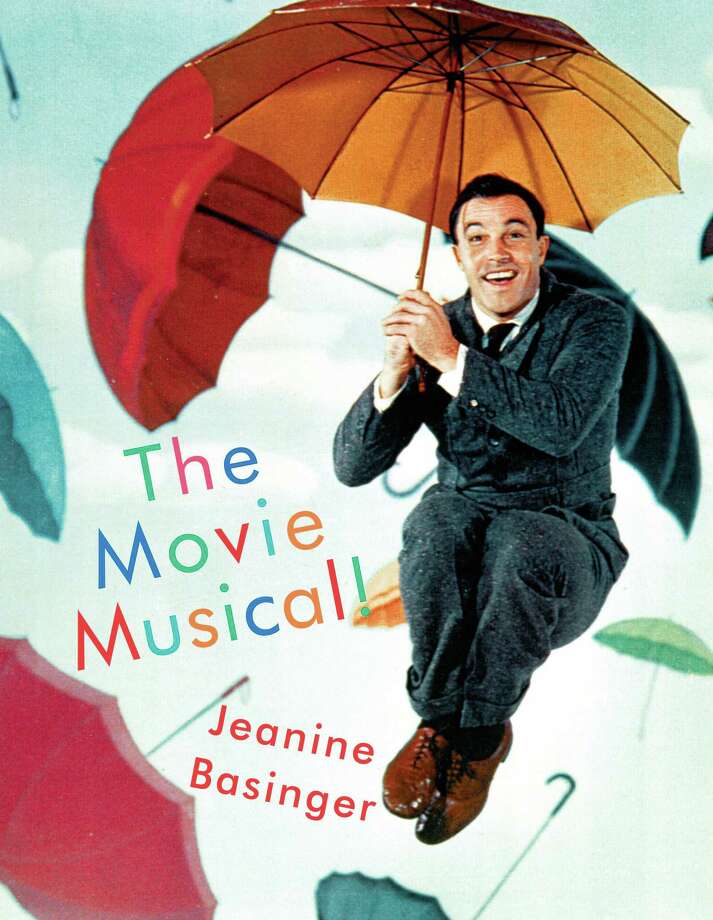

The Movie Musical!

The Movie Musical!

Photo: Knopf, Handout

The Movie Musical!

The Movie Musical!

Photo: Knopf, Handout

Book World: The glorious history of movie musicals

The Movie Musical!

By Jeanine Basinger

Knopf. 656 pp. $40

—

Some years ago, I took my young son to a touring production of “The Lion King.” He told me afterward that he’d liked it well enough “except for the parts when they were singing and dancing.” This disqualified the vast bulk of the show, but it put him squarely in the majority of my family, who would sooner die than watch someone erupt into song. And what a lonely vigil it can be, to be that minority of one, sneaking late-night YouTube peeks at the trash-can-lid dance from “It’s Always Fair Weather,” the Nicholas Brothers doing split jumps down a staircase, Ethel Waters singing “Happiness Is Just a Thing Called Joe.”

Yet we must be legion, we musical lovers, for the form persists, and here to remind us just how capacious it can be is “The Movie Musical!” The exclamation point signifies both the zeal that film historian Jeanine Basinger brings to her decades-spanning survey and the way in which the genre itself rises, without apology, above the mere declarative. Which is, of course, its glory and peril, for as Basinger writes: “When a movie becomes a musical, it must justify its musical performance; it has to create a reason for full-scale singing and dancing, because it is asking the audience to assume musical performance is natural.”

The central question, then, has been the same from “The Broadway Melody” (1929) to “Frozen 2” (2019): Why is somebody, in this very moment, choosing to perform for us?

In the case of the truly gifted, the answer is easy: We want them to. We don’t care what plot necessities require Judy Garland to open her mouth; the voice is the excuse. The character of Father O’Malley in “Going My Way” is a singing priest because that’s the only way we can be sure Bing Crosby will sing. The farcical complications that separate Fred Astaire from Ginger Rogers matter only in the moment when they clear and allow those two glittering figures to once more occupy a Bakelite dance floor.

Talent, in short, makes its own rules – which hasn’t stopped enterprising minds from devising rules of their own. Arthur Freed, the overseer of MGM’s greatest musicals, insisted that musical numbers had to advance the surrounding story. Rouben Mamoulian’s 1932 masterpiece, “Love Me Tonight,” created a fusion of music, character and plot so complete that, in Basinger’s judgment, it’s “never really been surpassed.”

In more recent times, filmmakers have concluded that musical performance is such an extravagance it can only be excused as fantasy. Which leaves us with the recent spectacle of “La La Land,” where two exceptionally attractive people imagine their love for each other by singing and dancing unexceptionally. Basinger has her own tart thoughts on that subject and plenty of other thoughts, too. Some are right on point. Crosby, who liked to ad-lib, “kept just outside the boundaries any film set up, and often undercut seriousness with a casual shrug or eyebrow lift.” Al Jolson “never looks a coactor in the eye. He keeps his own face turned to the camera, always looking out toward where he remembers is the place his audience would be located.” Basinger is particularly acute about choreographer Busby Berkeley, whose work is “the audience’s liberation from time and place.”

But anyone looking for a consistently bracing critical intelligence like Arlene Croce or Molly Haskell will find Basinger’s approach too rangy and scattershot. She has a habit of repeating herself. Garland is “one of the musical film’s most iconic figures” and “a legendary figure in Hollywood’s history” and “one of the most iconic figures in musical-film history.” Doris Day, we’re told three times in as many pages, can “put a song over.” Elsewhere, Basinger’s prose lapses into cliche – (“’42nd Street’ took audiences by storm,” Mario Lanza “took the country by storm”) – and fan-magazine gushing (Astaire “was a dancer who would become a movie star who would become a legend who would become immortal”).

She scants a lot of the Disney musicals, and she virtually ignores “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend,” the TV series that, better than any recent Hollywood product, has revivified the old song-and-dance tradition. Perhaps most seriously, she can’t decide in her summation if the classic musical needs to be emulated or outsmarted.

The real value of “The Movie Musical!” may just be to call the roll, invoking, yes, titans like Gene Kelly and Vincente Minnelli but also the host of ancillary talents who’ve diverted us through the years. By book’s end, closet musical lovers will have new treasures to carry back into their YouTube caves: Janet Gaynor crooning “I’m a Dreamer, Aren’t We All”; Alice Faye and Jack Haley chiding Shirley Temple with “You’ve Gotta Eat Your Spinach, Baby”; and, lest we forget, a Sonja Henie wannabe named Belita, who, for her big finish in “The Spirit of Victory,” skated to Beethoven’s Fifth before a gigantic copy of the Statue of Liberty. That’s entertainment.

—

Bayard is a novelist and reviewer whose most recent book is “Courting Mr. Lincoln.”