Cold Weather Company Courtesy of Tom Browning, Jr./Jersey Boy Photo

The singer stands alone on the stage with an acoustic guitar, leading his audience in a chorus of “Michael Row Your Boat Ashore.” The mostly over-50 crowd joins in with enthusiasm. A smattering of young couples with children also sing along. Close your eyes, and you might think you’re back in the 1960s. In fact, the concert, a tribute to the late folk-music pioneer Pete Seeger, is taking place on a lazy spring Sunday afternoon at the Montclair Public Library. Onstage is Spook Handy, a New Brunswick-based folk singer and a central figure of New Jersey’s acoustic-music scene.

Spook Handy Courtesy of Mark Lamhut

Folk music endures in New Jersey largely because of intrepid artists like Handy and a loyal audience of mostly baby boomers who turn out for performances in small clubs, cafes, local living rooms and other alternative venues.

Handy’s Seeger-inspired style represents one of the flavors on the New Jersey folk landscape. But a genre as loosely defined as folk fosters many variations among Garden State musicians.

A case in point is the Middlesex County-based trio Cold Weather Company, whose independent alternative folk is influenced by contemporary artists like Bon Iver, the Decemberists, and Iron and Wine. On the Cold Weather Company website, guitarist Brian Curry describes the band’s willingness to deviate from folk orthodoxy this way: “Music is music, and sonic growth and exploration are essential to artists.”

Some acts have a foot in both the traditional and contemporary camps, such as the Ocean County-based folk duo Jackson Pines. They describe their sound as “original singer-songwriter indie folk music.” While blazing their own trail musically, the members of the group are still influenced by the past. “Pete Seeger is the reason why we do what we do,” says guitarist/vocalist/songwriter Joe Makoviecki. “He’s the reason that I decided to pursue the band full-time, for real.”

Longtime concert promoter John Scher, who has been putting on shows in the metropolitan area since the 1970s, observes, “You’ve got a blending right now of the old and the new, and I think it will always be there.”

Abbie Gardner Courtesy of Brian McCloskey

New Jersey folk artists can be heard in places both likely and unlikely. Clubs and coffee houses provide some opportunities for gigs, but most performances take place at one-off events at libraries and churches, living-room house concerts, outdoor town music series, warm-weather festivals, and concerts staged by long-running volunteer organizations.

Mike Herz Courtesy of Brian McCloskey

“When push comes to shove with venues and clubs, it’s about running a profitable business,” says Mike Herz, a singer/songwriter from the Sussex County town of Newton. “They know that they have a bigger chance of getting more people in there if they have a band. And people will buy more alcohol if there’s a band.”

For folk artists hoping for club gigs, it helps to be near a town with a vibrant music scene, such as Asbury Park. The seaside resort has long been a haven for musicians, and many of its clubs and other venues are open to a range of styles, including acoustic music.

“I do a lot of shows in Monmouth and Middlesex counties, and particularly in Asbury Park, because they’re very friendly to original music,” says singer/songwriter Dave Vargo. “The Saint [in Asbury Park] is the kind of venue that will typically have two or three acoustic shows a month. They’ll hire acoustic openers once again for touring bands to come in and be the opening spot. The Asbury Hotel, which is a newer venue, has been very, very good with that as well.”

In Jersey City, the burgeoning club scene is augmented by open-mic nights, songwriter showcases and a major concert venue, White Eagle Hall. There’s also the annual Hudson West Folk Festival, taking place this year on September 14 at Grace Church.

“I feel like a lot more opportunities to play are popping up everywhere,” says Abbie Gardner, a Jersey City-based singer/songwriter who accompanies herself on Dobro (a resonator lap guitar played with a slide) and is also a member of the trio Red Molly. While fans in Jersey City mostly used to travel to New York for music, the reverse is now happening, too. “We have a lot of people crossing the river from New York,” Gardner says.

New Brunswick also boasts a lively music scene. “New Brunswick has a lot of really cool artists,” says Cold Weather Company’s Steve Shimchick, who met his bandmates—Brian Curry and Jeff Petescia—while attending Rutgers. They still live in the New Brunswick area, but tour all over.

Even in a musical hotbed like New Brunswick, Shimchick says, only a couple of clubs—he cites Scarlet Pub and Barca City—book acoustic acts. As a result, he says, “[unofficial] basement shows are still a huge thing, and more venues are offering open mics and opportunities for developing artists.” The folk community, he adds, “is super close and supportive.”

Throughout the state, alternative venues provide exposure for folk musicians. These include several notable small concert halls and listening rooms. Albert Music Hall in Waretown is perhaps the best known. A haven for traditional music, it has run a regular Saturday-night show for many years.

Dave Vargo Courtesy of John Cavanaugh

“It’s definitely one of the oases of folk music in New Jersey,” says Makoviecki of Jackson Pines. “Albert Hall definitely had a big influence on teaching us how to play, how to keep an audience excited and get their attention, and just how to be better musicians.”

Another is the Lizzie Rose Music Room, a nonprofit venue in the Ocean County town of Tuckerton. It typically runs seven or eight shows a month in a mix of genres heavily weighted toward folk and acoustic music. The venue puts on a regular songwriter’s night hosted by East Brunswick native Dave Vargo. Some of the songwriters showcased at Lizzie Rose Music Room also get to open for the touring headliners.

Vargo also hosts the Pierce Sessions, a Tuesday-night songwriter showcase at the Pierce Memorial Presbyterian Church in Farmingdale in Monmouth County.

Local nonprofit volunteer organizations have long played a key role in bringing folk music to their communities. The Folk Project is one of the busiest and most prominent. It’s best known for its weekly Friday-night concerts, recently re-christened the Troubadour Acoustic Concert Series. The shows take place at the Morristown Unitarian Fellowship and feature a mix of performers, local and national.

The Folk Project, founded 43 years ago, has more than 500 members, many of whom are musicians. “The Folk Project and the Troubadour were organized by New Jersey musicians to serve local artists and provide venues for their expression,” says Mark Schaffer, one of the group’s organizers. “Local performers are integral to everything we do and the backbone of our volunteer staffs. The Troubadour does four member nights every year, each featuring 24 songs by about 50 performing members.”

A monthly open stage provides further opportunities. “It features 40 local musicians performing all night on two stages in concert format,” says Schaffer.

Montclair’s Outpost in the Burbs started as a coffee house in 1987 and has become a significant stop for touring musicians, including acoustic acts. Outpost puts on roughly 20 shows per year at the First Congregational Church, where the sanctuary can hold up to 750 people.

“Artists being New Jersey-based is definitely one factor I look at in making booking decisions,” says Outpost’s talent buyer, John Hammond. “I also consciously made a point to expand our booking strategy to encompass other vibrant musical scenes in the state, including the Shore area and South and Central Jersey.”

Teaneck’s Ethical Culture Society is home to another notable folk series, Ethical Brew, which puts on eight to nine shows a year.

“Our focus is generally emerging singer/songwriters, duos and trios,” says Beth Stein, who runs Ethical Brew with her husband, Perry. “We offer a wide range of music from traditional folk and Americana to cutting-edge indie performers.”

Ethical Brew brings in touring acts and New Jersey-based performers, including Beppe Gambetta, Katherine Rondeau, Josette Diaz and Frank Lombardi, among others. It’s more than just a music series, though. “We are an all-volunteer operation,” says Stein. “Proceeds from every show are split between the Ethical Culture Society—to fund its social-action projects—and a partner charity designated by the performer.” Similarly, Montclair’s Outpost supports a local food kitchen and promotes volunteerism.

House concerts are another essential cog in the New Jersey folk scene. Bill Brandenburg, who books several town-sponsored concert series in Woodbridge, in Middlesex County, says house concerts have been “a savior” for acoustic music in New Jersey. “They provide a place where people can play and make a few dollars and get exposure for their music.”

House concerts typically take place in the host’s living room and allow an intimate connection with the audience. “I don’t use a sound system,” says Brenda Wirth, who runs Rosie’s Cafe Concerts in Brick, a series named after her late dog, Rosie. “People are literally a couple of feet away from the performer.”

House concerts are generally not advertised, are publicized mainly by word of mouth, and require advanced reservations. Most have Facebook or web pages that list upcoming shows. The events often feature potluck meals where the audience members can mingle with each other and the artists.

Other notable New Jersey house concert series include Cozy Cabin Concerts in Green Brook; Concerts in the Studio in Freehold; and Notes From Home in Montclair.

Jackson Pines Courtesy of Michael Ryan Kravetsky

A number of clubs and coffee shops around the state offer regular open-mic events. Most take place on weeknights, with the occasional Friday or Saturday show. The quality of the performers varies, but the events are essential networking opportunities for the participants and offer musicians a way to build local exposure. “Open mics open doors,” says Makoviecki of Jackson Pines.

“The most beautiful aspect is the friendships that are forged and the musical collaborations that are created as a result of playing the open-mic circuit,” says singer/songwriter Meg Beattie Patrick, who has run two open mic series in the Montclair area.

Sharon Goldman

Some notable open mics take place at Expresso Joe’s Sunshine Café in Keyport; Dragon Fly Music and Coffee Café in Somerville; FM and the Corkscrew Bar in Jersey City; and Hidden Grounds in New Brunswick. (Expresso Joe’s and Dragon Fly also schedule occasional folk shows.) Open mics pop up all over; you can find them through openmicnewjersey.com.

Unfortunately, open mics don’t pay anything and are generally on off-nights, when the crowds are relatively small. Trying to get paid bookings at well-attended venues is difficult in any genre, but for New Jersey folk musicians, it requires an especially high level of persistence and industriousness.

“People think of New Jersey as being a place where you know you’re going to the bar to hear someone play covers,” jokes Metuchen-based singer/songwriter Sharon Goldman. “I admire folks that do that—it’s a skill. I do sing covers, and many folk singers do, but I am personally a songwriter and not interested in being a cover artist. So, you know, you have to be creative.”

Because of New Jersey’s proximity to New York City—long a folk-music mecca—its role in the history of folk music is often overlooked, but many important events and performers have ties to the Garden State.

Because of New Jersey’s proximity to New York City—long a folk-music mecca—its role in the history of folk music is often overlooked, but many important events and performers have ties to the Garden State.

Any history of New Jersey folk would have to start with the Pine Barrens, which was a melting pot of traditional folk music as far back as the 1700s. In his book New Jersey Folk Revival Music: History & Tradition (History Press, 2016), author Michael C. Gabriele says the Jersey Pinelands were a central location where Northern and Southern folk-music traditions blended.

The city of Camden also played a vital role in New Jersey folk-music history. It was the home of Victor Studios, which was the site of many important folk recording sessions. In 1925, Paul Robeson made some of his earliest recordings at Victor, and the Carter Family recorded there in 1928. Jimmie Rodgers, aka the Singing Brakeman, recorded there several times, including in August 1932, less than a year before he died of tuberculosis.

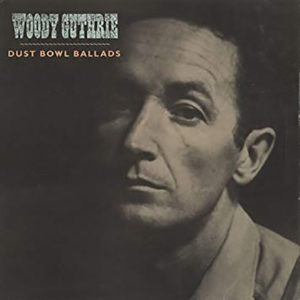

And then there was Woody Guthrie. “Woody Guthrie’s first commercial album [Dust Bowl Ballads, 1940] was recorded at Victor; not Oklahoma, not Texas,” says Gabriele. “It was made up of songs about him rambling around Oklahoma when the Dust Bowl hit, and he recorded it in Camden, of all places.”

Guthrie also spent a lot of time in East Orange, but unfortunately, it was mainly during his decline from Huntington’s disease. In 1961, when he was hospitalized at Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital in Morris Plains, he frequently spent weekends at the East Orange home of his friends Bob and Sid Gleason. In both places, he was often visited by a 19-year-old novice named Bob Dylan, who referenced the meetings in his song “Talkin’ New York” with the words, “So long New York. Howdy, East Orange.”

Other notable Jersey folk musicians include Janis Ian, who attended high school in East Orange, and the Roches, a vocal trio of sisters from Park Ridge, whose heyday came in the 1980s and ’90s. John Gorka, another prominent Jersey folk artist, was born in Woodbridge and established himself during the fast-folk movement of the 1990s.

And don’t forget Bruce Springsteen. Though a rock icon, he also has his folk influences and is, at his core, a singer/songwriter. His 2006 album, We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, was comprised of songs associated with Pete Seeger.