M

y sobriety began with a jump, falling into murky water. That’s not a metaphor: swimming in the middle of nowhere in my native South Africa in 2012, I picked up a parasitic disease called bilharzia; my subsequent weakened immune system and a summer of binge-drinking led to a case of hepatitis. Both diseases required prolonged hospital stays and strict admonishments against drinking alcohol. My nightly drinking and smoking were replaced with green tea and rest.

Three months of rest on doctor’s orders turned into eight years and counting. I left my old self at the bottom of that river, along with my old career and a few drinking buddies. As I transitioned into the life of a full-time writer over those years, I wondered whether it was possible to have a dynamic creative life after you get sober: can an artist relish the routine instead of the riot? The image of the drunk, drugged rock’n’roll life has helped to normalise addiction, after all. Sobriety and creativity cast a complex picture that asks more questions the longer you stare at it. I spoke to three musicians at different stages of their sober journey about leaving drink and drugs behind.

Jason Isbell‘You romanticise the addiction’ … Jason Isbell performing in March. Photograph: Amy Harris/Invision/AP

Country music star Jason Isbell has spent more than half a decade without drugs and alcohol. “I wanted an excuse to disconnect, and once that excuse was gone, I had to start the process of figuring out why I needed to connect in the first place,” says Isbell, 41. “When I got sober, I was able to pay attention to the world more, and awareness is the most important tool for any creative person. When you’re working so hard to numb your brain, very often you throw the baby out with the bathwater. You miss things that you really needed when you sat down to write that song.”

Isbell was eminently familiar with the self-justification that leads many artists to drink. “You romanticise the addiction and say, ‘Well, Hemingway,’” he says. “But that’s just the addicted part of your brain. When I started writing a song after getting sober, I realised I wasn’t really afraid of losing my creativity. I was just trying to have another drink.”

Making art without substances can bring substance back to your art, and Isbell has shared his experiences with peers who are anxious about the creative implications of getting sober. He compares himself to Tom Dowd, who worked on the atomic bomb in the Manhattan Project at 18 years old. “He came back to college after splitting the atom and had to sit in class and listen to his professors teach pre-nuclear physics,” Isbell explains. Dowd’s own work had contributed to disproving these concepts, but he was ordered by the government not to talk about it. Eventually, he quit college to make music. “When somebody who’s still drinking wants to talk about sobriety, I let them know I’ve seen the science behind this, and that what they’re worried about isn’t real,” he says. “It’s like taking your toddler to the closet before they go to bed, and showing them there’s nothing in there. For my daughter, those shadows are ghosts. But to me, they’re just shadows. They’re colours on the wall.”

Bethany Cosentino, Best Coast ‘I learned how to take care of myself through sobriety’ … Bethany Cosentino, with Bobb Bruno of Best Coast. Photograph: Kevin Haynes

‘I learned how to take care of myself through sobriety’ … Bethany Cosentino, with Bobb Bruno of Best Coast. Photograph: Kevin Haynes

Three years ago, Bethany Cosentino of indie-rock band Best Coast started work on the band’s new album, Always Tomorrow. Six months later, she decided to get sober. “We’re seeing so much more burnout from artists, but I learned how to take care of myself through sobriety,” says Cosentino, now 33. “We live this very Groundhog Day existence when touring, and there’s a lack of self-care or even acknowledging the exhaustion. We think of a bottle of wine or a handful of pills or a joint as a break, but that’s not self-care.”

In 2010, Best Coast made their name with songs about getting high and drinking at the beach. Removing the haze of drugs and alcohol reshaped Cosentino’s perspective. “The window on the album cover is the window I was sitting directly in front of while writing,” she says. “I remember looking out at the landscape, seeing the mountains and the sun and the buildings in the distance and thinking, ‘I know that this has been there all the time, but I never noticed it before.’ I went through life with such a veil over my eyes. I now truly feel in tune with the universe and the rhythm of life because I’m experiencing it in its raw and natural form.”

Talking about her decision to get sober was nerve-racking, says Cosentino, “because it is still relatively new and so personal”. But she pushed through her discomfort. “The more that people talk about sobriety and mental health issues, the more we are comfortable with this conversation.”

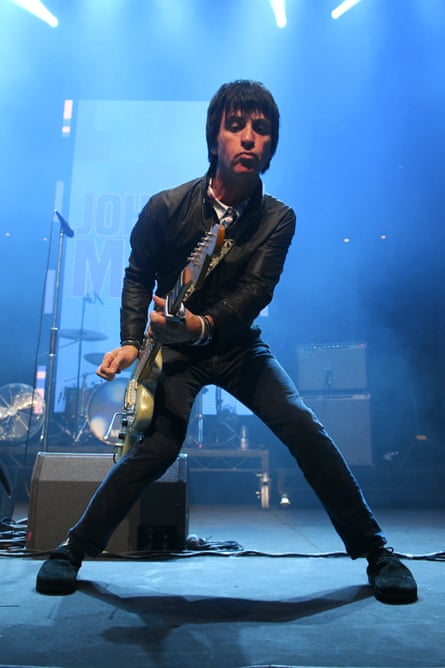

‘Quitting boozing meant I had more time on my hands’ … Johnny Marr performing in September 2019. Photograph: David M Benett/Getty ImagesJohnny Marr

‘Quitting boozing meant I had more time on my hands’ … Johnny Marr performing in September 2019. Photograph: David M Benett/Getty ImagesJohnny Marr

Johnny Marr stopped drinking in the mid-2000s, determined to make the most of his energy and eschew the cliche of the ageing, wasted rock star. “The paradigm in rock that sobriety equates to conservative is very out of date,” says Marr, who is 56. “If you’ve got artistic tendencies, ideas and talent, eventually you get to the place with booze and drugs where you become the opposite.”

Before he quit drinking, Marr would regularly head to the pub or get stoned at home. “I thought it was an achievement if I didn’t get fucked up one night during the week,” he says. “That’s not an achievement. Writing a song is an achievement. Teaching kids, caring for someone, or pulling someone out of a bloody burning building is an achievement.” When he realised he was endlessly seeing the world through the same perspective and stopped drinking, his creativity rocketed. “There was no downside,” says Marr. “I started writing a hell of a lot of songs for Modest Mouse. Quitting boozing meant I had more time on my hands. I felt better and had more energy. I always regard that time as being the best time of my life.”

And where some may shrug off sobriety as boring, Marr insists a bit of boredom is essential for good work. “Boredom is the main wellspring of creativity,” he says. “If you obliterate that, you’re denying yourself a great opportunity.” He became an active long-distance runner, and sped up in every sense. “My music and my life would have been much slower-tempo if I hadn’t gotten sober,” says Marr. “There’s a time and place for that – in your late 60s, please God.”