The 2012 documentary film Beware of Mr Baker is a profoundly discomfiting watch. The adjective regularly used to describe its subject is “cantankerous”, but that isn’t really right. Cantankerous sounds like a word you would append to a beloved but grumpy old relation, and – in the film at least – there’s nothing lovable whatsoever about Ginger Baker.

Sequestered in his South African compound, he seems authentically horrible: rude, obnoxious, arrogant, dismissive, violent. It doesn’t seem to be an act put on for the camera. His children’s relationship with him is clearly strained – on one occasion, his son recounts, they played a gig together that entailed his father giving the 15-year-old a line of cocaine, then absconding with their fee, leaving him stranded. His latest partner stares blankly and silently at the camera when asked whether he’s a good stepfather. Even the man he describes as “his best friend in the world”, Eric Clapton, seems to regard him with a very wary eye: he “doesn’t know him well”, he says, before describing him as “scary, threatening … difficult”. It’s hard not to find yourself wondering aloud why anyone would want to have made a film about Baker, simply because doing so would have meant spending time in his company.

The answer, of course, lay in the music Baker made in the 1960s and 70s. By common consent, he helped to redefine the notion of the rock drummer, elevating the role from that of time-keeping backing musician to a star attraction. Devotees of Ringo Starr and the late Keith Moon – about whose playing Baker was characteristically contemptuous – might argue that he didn’t do it singlehandedly, but there’s no doubt that Baker’s style of playing had an enormous impact.

Cream … (from left) Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, Eric Clapton. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

He was also, on occasion, a musical visionary. He was among the first British musicians to cotton on to the revolutionary sound of Afrobeat being pioneered by Fela Kuti. Commendably unwilling simply to decorate his own music with Nigerian inflections, he immersed himself in Kuti’s world, moving to Lagos, joining Africa ’70 and setting up his own recording studio.

You could hear Baker’s jazz training on the records he cut with his first band, the Graham Bond Organisation, but he came into his own when he left Bond to form Cream. The gulf between the music on the Graham Bond Organisation’s album The Sound of 65 and Cream’s debut, Fresh Cream – recorded barely a year later – speaks volumes about the speed at which pop was moving in the mid-60s. The former is gritty but musicianly jazz-flecked rhythm and blues; the latter is expansive, experimental, heavily improvised and genuinely groundbreaking. You can hear the roots of everything from heavy metal to jam rock to the power trio format subsequently adopted by umpteen bands in its nine tracks.

Cream’s free-thinking approach to rock gave Baker space to thrive. Fresh Cream concluded with his track Toad, a five-minute showcase for his talents. Most rock drum solos are indescribably boring, but Toad is thrilling, testament to Baker’s patented cocktail of swing, control and wildness.

Cream’s catalogue is filled with examples of Baker’s rhythmic invention – he transformed the single White Room by adding a “Bolero” section in 5/4 time – and the trio were a sensation, albeit a short-lived one. Before the release of their third album, Wheels of Fire, and barely 18 months after their debut, the band had split. Part of the problem was sheer exhaustion from touring and the band members’ boredom with the ever-increasing volume of their live shows. But you might have predicted the band wouldn’t last long from the start. Baker and bassist Jack Bruce had played together in the Graham Bond Organisation and loathed each other – Bruce had quit after Baker pulled a knife on him – a state of affairs not much helped by Baker’s longstanding heroin problem.

Next, he joined Clapton and Steve Winwood in the short-lived supergroup Blind Faith, whose solitary album suffered both from hype and the sense that it was recorded in a rush. An underrated and idiosyncratic writer, as evidenced by Cream’s Blue Condition and Pressed Rat and Warthog, Baker’s Do What You Like had the makings of a charming song, but was allowed to ramble, unfocused, for 15 minutes. Not even a drum solo could save it.

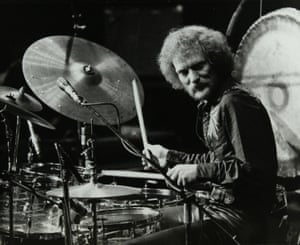

Ginger Baker performing at the Forum theatre, Hatfield in 1980. Photograph: Heritage Images/Getty Images

Blind Faith barely lasted long enough to complete a US tour, but Baker – frequently the onstage focus rather Winwood or the increasingly reticent Clapton – apparently enjoyed the experience, subsequently attempting to repeat the supergroup formula with Ginger Baker’s Air Force, ominously named after the section of Duke Ellington’s orchestra comprised of heroin addicts. Recorded live, their eponymous debut was muffled, patchy and once again, wildly over-hyped, but it offered up a game and groundbreaking attempt to meld rock with jazz and the African music with which Baker was increasingly obsessed. A second, studio-recorded album also had moments when the fusion of styles gelled perfectly, not least the potent Graham Bond-penned closer 12 Gates of the City, but the Air Force’s music simply wasn’t commercial enough to bear the weight of expectation placed on it, nor the cost of transporting its vast lineup – which at one stage featured three percussionists – around on tour.

By 1971, Baker was in Lagos, building a recording studio and collaborating with Fela Kuti, whom he’d known since the early 60s, when Kuti – then studying in London – had begun hanging around Soho’s jazz and blues clubs. A tireless booster of Kuti’s work, Baker had helped him get gigs around London while still a member of Blind Faith. His work with Kuti and Africa ’70 seemed to provide Baker with a respite from his post-Cream role as “superstar drummer”. He got front-cover billing on Fela With Ginger Baker Live! and Kuti’s subsequent studio album Why Black Man Dey Suffer, but what’s striking about both is how seamlessly Baker fitted into Africa ’70, happy for his contributions to be subservient to the band’s fluid, polyrhythmic groove. A subsequent reissue of the former added a live drum duet between Baker and Kuti’s regular percussionist Tony Allen, but for the most part, you wouldn’t have noticed that the man behind Toad was there at all.

Kuti returned the favour, appearing on Baker’s solo album Stratavarious, a fantastic psychedelic Afro-rock confection that demonstrated how intuitively Baker grasped Nigerian music, but his African sojourn eventually came to grief. Stories about exactly what happened vary, but the upshot was Baker losing his studio and fleeing the country virtually penniless. He seemed to join yet another “supergroup”, the Baker Gurvitz Army, primarily out of financial necessity. There’s nothing exactly wrong with their three albums of straightforward hard rock, but their contents are a long way from the innovations of Cream or Afrobeat or Stratavarious.

After their split, Baker’s life seemed to descend into chaos, shot through with further tales of financial mismanagement and personal turmoil. He played on Hawkwind’s 1980 album Levitation – you can spot him a mile off on Space Chase and closer Dust of Time – but otherwise largely retreated from music. Producer Bill Laswell involved him in the making of Public Image Limited’s acclaimed 1986 album Album and had him record an instrumental solo album, Horses and Trees, that veered from world music fusion to experiments with sampling and scratching. However, by the late 80s, Baker was reduced to placing small ads in LA music magazines, looking for work.

He spent the rest of his career dividing his time between session work and a succession of intriguing, if uneven, solo projects that lurched between world music (Ginger Baker: African Force), free improvisation (Unseen Rain; No Material, a challenging collaboration with saxophonist Peter Brötzmann and others) and jazz: Going Back Home (1994) and Coward of the County (1999) both received critical praise, underlining that, unlike most of his rock peers, Baker could cut it as a straightforward jazz drummer.

Grim image … Ginger Baker in 2008. Photograph: David Levene/The Guardian

A brief Cream reunion in 2005 ended unhappily. Baker and Bruce’s enmity had not been dimmed by the passing of time, Bruce wryly suggesting that things might be improved if Baker moved even further away from England than his new home in South Africa. Then came Beware of Mr Baker and a series of promotional interviews for the film that did nothing to undercut the grim image projected in it. It was hard to work out whether Baker was just spectacularly embittered by his experiences in the music business, or whether he’d always been a bit like that.

Whatever the reason, Baker was clearly not an easy man to love, or even to like. But he was also an inspired and groundbreaking musician, a drummer other drummers queued to pay homage to, even when their praise was rebuffed. And that’s what Baker should and will be remembered for. “He wanted to advance and challenge himself – isn’t that what we’re all doing this for?” offered John Lydon, decades after the two had collaborated, noting that he was also “a nutter … a monster-raging-crazy-loony”. “We just gelled,” he added.